The Commissioning of the PG-21

by Michael Mayo

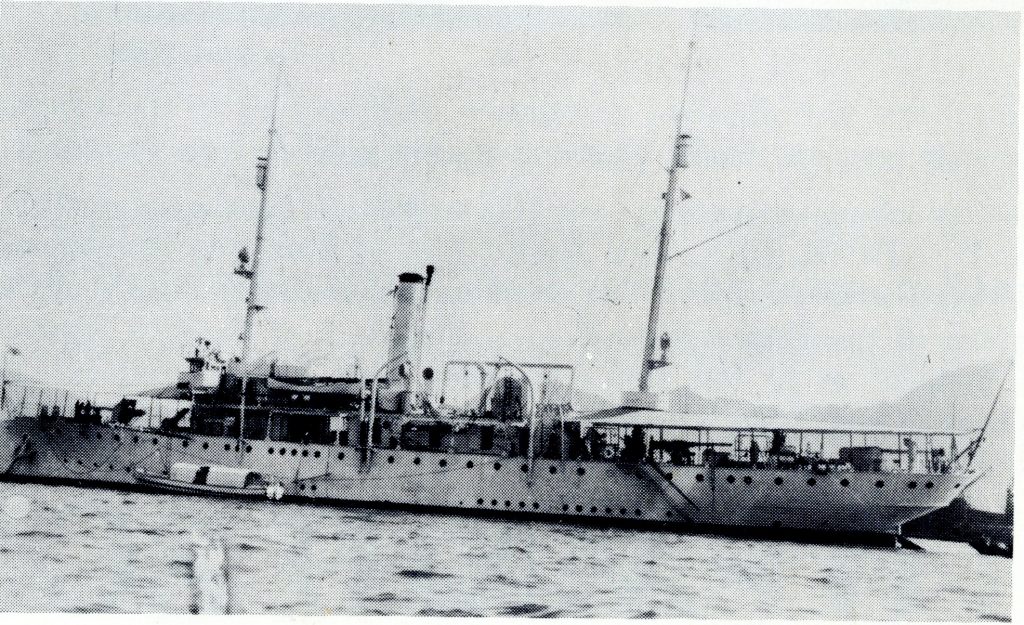

The PG-21 was borne of the efforts of the city of Asheville’s leadership to promote Asheville as an up-and-coming town, relevant to the United States’ new status as a world power and to its expanding navy. In some ways, the city working for the ship to be named in its honor was staking a claim against Wilmington and Charlotte for prominence as an urban center; Asheville was, in 1918, the third largest city in the state trailing behind both Wilmington and Charlotte. Wilmington is actually on the water and Charlotte was, even then, an important financial center, but neither of the two had ships named after them. The fact that North Carolina’s Josephus Daniels was Secretary of the Navy under Woodrow Wilson may have also influenced the city leadership’s decision to push for the PG-21 bearing Asheville’s name, as a means of elevating both the city and their personal careers in state politics. Community leaders personally witnessed the ship’s 4th of July, 1918 launching at the Charleston, South Carolina shipyard which was recorded in the Asheville Citizen-Times.2

The Career of the PG-21

by Gillian Cobb

After her commissioning, the PG-21 served in the Caribbean waters from 1920 until 1922, as a part of the Special Services Squadron. In 1922, most of the ship, excluding the galley, was converted from a coal burner to be an oil burner. Later that year, she departed from Charleston, SC, to join the Asiatic Squadron. In September of 1922, the PG-21 had reached Manila, Philippine Islands. She served this area for 7 years, monitoring United States interests.3 In 1929, The Asheville returned to the Caribbean as a part of the Special Services Squadron, but later returned to the Asiatic fleet in 1932. The Asheville began her patrol of the 2,000 mile Chinese coast.

During this time, many sailors described the conditions on the ship to be “primitive.”4 The old washroom aboard had no shower, only an old farm water pump. Engine trouble also plagued the ship for years. In July of 1941, the Asheville had to be towed to the Philippines for repairs.

In 1941, all gunboats, including the Asheville, were recalled to Manila Bay. By December 10th, the U.S.S. Asheville and the U.S.S. Tulsa were ordered to Java.

The loss of the PG-21

By Jordan Allan

While in the contested waters off the Javan coast, the Asheville spent its time serving under Dutch Command. Its primary duty was in protecting merchant ships from the ever present threat of the nigh-invisible menace, the submarine. Although it was undoubtedly a tense job, the USS Asheville saw very little combat duty.

This all changed on the 1st of March, 1942, when an order was given for all Allied forces in the area to rendezvous 500 miles south of Java, in order to head for Australia with safety in numbers. Concerned by the lack of encryption (if the Japanese read the transmission, the Japanese could place ambushes anywhere alongside the designated route), a decision was made to split the fleet up, skip the rendezvous, and head directly to Australia. The Asheville would leave the Javan port city of Tjilajap with the fellow gunboat, the USS Tulsa. In the Second World War, the oceans had become a battlefield, and any journey through them was going to be a risk. Unfortunately, the following day, the Asheville’s notoriously ornery engine began to cause trouble at the worst possible time. Unable to keep up with the Tulsa, the Captain’s of both ships made a mutual agreement to part ways. The Tulsa would continue heading for Australia, and the Asheville would risk meeting at the rendezvous point. Both ships were now alone.

On March the 3rd, the Asheville was intercepted by the Japanese taskforce of 3 cruisers, and 3 destroyers. Although the USS Asheville did its duty and engaged the enemy, it never had a chance. The ship was lost, seemingly with all hands. It was the first ship to go down with its full crew complement since the surprise attack at Pearl Harbor.

There was one initial survivor: Fred Brown, a firefighter from Ft. Wayne, Indiana, who was plucked out of the water as a prisoner by Japanese sailors. Brown was placed in a prison camp alongside other allied Prisoners of War, where he remained until March of 1945, where he passed away from a combination of malnutrition, pellagra, and heart disease.

This was not the end of the Asheville. When Ashevillians heard the news that the gunboat named after their city had disappeared (its destruction had not yet been reported), an enlistment rally was organized, and 160 new men were enlisted.5 On March 10 of 1942, a new USS Asheville was laid down, an Asheville-Class Patrol Frigate.6

Specifications7

- Displacement: 1,575 tons

- Length: 241’2″

- Beam: 41’2″

- Draft: 11’4″

- Speed: 12 knots

- E.L. Hupp, Box M1999.02.2.9, Folder M99.2.2.9, U.S.S. Asheville PGM-84 Commemorative Booklet, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- W. Eric Emerson, The USS Asheville and the Limits of Navalism in Western North Carolina (The North Carolina Historical Review 89, 2012); E.L. Hupp, Box M1999.02.2.9, Folder M99.2.2.9, U.S.S. Asheville PGM-84 Commemorative Booklet, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, Box M1999.02.08, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- Walter Ashe, U.S.S. Asheville Narrative, Box M99.2.1.1, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- Bill Moore, “Remembering USS Asheville’s Last Voyage,” Asheville Citizen-Times, August 5, 1984, Box 1, Folder 2, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- Bob Terrel, “USS Asheville Remembrance Being Set Up,” Asheville Citizen-Times, May 13, 1984, Box 1, Folder 2, Walter Ashe Collection, D.H. Ramsey Library Special Collections, University of North Carolina at Asheville, Asheville, NC.

- “NavSource Online: Gunboat Photo Archive,” Accessed April 1, 2019, NavSource